By Ishaan Tharoor

with Claire Parker

A worker carries printed editions of Bild newspaper that show candidates for chancellor Olaf Scholz and Armin Laschet after the first exit polls for the general elections in Berlin on Sunday. (Andreas Gebert/Reuters)

The one certainty going into Germany’s elections on Sunday was that they were bound to yield a period of uncertainty. Ahead of the vote, polls suggested a narrowing race between the country’s two waning political heavyweights — the center-left Social Democratic Party and the center-right Christian Democratic Union of long-ruling (and outgoing) Chancellor Angela Merkel — as they sought to also stave off the challenge of other parties, including the Greens and the laissez-faire Free Democrats. Whatever the outcome, the country would have to endure weeks, or even months, of protracted coalition talks between rival parties jockeying for power.

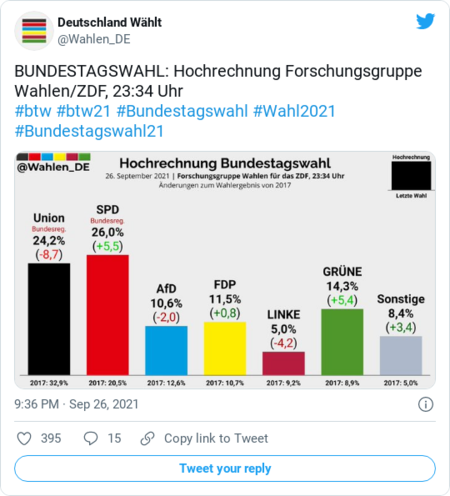

At the time of writing, little else is clear. The Social Democrats, or SPD, had a slender two-point lead over the Christian Democrats, with the Greens and the FDP posting strong showings ahead of the far-right Alternative for Germany. But no decisive mandate has emerged. Olaf Scholz, SPD front-runner and Germany’s current finance minister, told reporters that he hoped to rule out a scenario where Merkel delivers the chancellor’s customary Christmas speech this year with parties bogged down in extended negotiations over the next government.

My colleagues charted a guide to the various coalition options, which derive their names from the amalgamation of each party’s colors into one bloc. The “traffic light” coalition — red, yellow and green — would see an alliance between the SPD, Free Democrats and Greens. That may be the first bloc that Scholz hopes to assemble, but significant ideological differences could throw a spanner in the works. An alternative “Jamaica” coalition — black, yellow and green, like the flag of the Caribbean nation — could see Scholz and his allies get supplanted by the Christian Democrats. A “Jamaica” coalition almost came to power in 2017, before FDP leader Christian Lindner pulled the plug and walked away. The country’s center-right and center-left found themselves once more in an uneasy alliance neither really wanted.

Even now, one can’t rule out a “Kenya” coalition, where the SPD and Christian Democrats restore the grand coalition that held sway under Merkel for much of the past decade, augmented this time by the third-place Greens. Less likely — but still on the table — is a left-wing government of the SPD, Greens and the far-left Die Linke (or the Left), which traces its roots to East Germany’s former ruling Communists.

Other permutations are possible. Smaller parties will play kingmaker as negotiations proceed, holding the portfolios of key ministries as collateral. They may feel the political winds blowing in their direction as both the SDP and CDU hemorrhaged young voters to the Greens and FDP. Analysts pointed to the increasing “Dutchification” of German politics — a nod to the steady fragmentation of traditional party politics next door where once-dominant 20th century factions have lost considerable ground to newer upstarts. Sensing their budding power, the Greens and FDP are expected to negotiate with each other before hitching their wagon to one of the two bigger parties.

Preliminary results are expected Monday morning. But the Christian Democrats appear poised to mark a historic low — a poor performance that can, in part, be laid at the feet of Armin Laschet, the candidate tapped by the party to succeed Merkel but who ran a campaign marred by gaffes. According to exit polls, Merkel’s party lost votes to the SPD, with Scholz appearing to many Germans to be a more plausible figure of stability and continuity than Laschet. With Merkel exiting the political stage, the constituency she held since 1990 was won by an SPD challenger.

“This will be a long election night,” Scholz said Sunday evening. “But what’s also clear is that a lot of voters cast their ballots for the Social Democrats because they want a change in government and also because they want the next chancellor to be called Olaf Scholz.”

But there’s a long road ahead before Scholz can claim the mantle of leadership. The most plausible arrangement — the “traffic light” coalition with the Greens and FDP — will require hard political bargains between Scholz and his would-be partners. Lindner may prove especially problematic: Scholz recently dubbed his views on cutting taxes as “morally difficult to justify.” And Lindner’s belief that the fight against global warming should be left to the incentives of the free market was explicitly rejected by Annalena Baerbock, the Greens’ candidate for chancellor.

“At this point in time, I actually lack the imagination as to what Mr. Scholz and the Greens could offer the FDP that would be attractive to us,” Lindner told supporters at a recent rally. But that may simply mark the opening salvo in tense negotiations to come.

All the while, Europe’s biggest economy and arguably most important political player will find itself in a kind of limbo. Merkel anchored years of German political stability, but she was also a European bulwark — an unofficial leader of the continent who helped steer it through cycles of political and economic crisis.

“Merkel’s exit creates a problem with leadership, a hole at the heart of Europe,” said Giovanni Orsina, director of Luiss Guido Carli University’s School of Government in Rome, to my colleagues. “Either the new chancellor fills that void, or we need to conceive of a collective convergence.”

But Germany arguably may need to move on beyond the Merkel era. Jens Geier of the Socialists & Democrats group in the European Parliament told Politico that a German government led by Scholz would play a “much more active role in Brussels.” Merkel’s critics “say she delayed decisions at the E.U. level in an effort to preserve consensus and avoid conflict — and while doing so allowed for the erosion of democratic norms in countries such as Hungary and Poland,” my colleagues noted. “Her approach even earned its own verb: ‘Merkeln,’ meaning to dither or bide one’s time.”

“Whereas Merkel sought equilibrium, the incoming government will have to make key decisions that will force it to pick sides on the international chessboard,” wrote Aaron Allen of the Center for European Policy Analysis, gesturing to long-standing debates over Germany’s relations with countries like China and Russia. “In any case, many Germans have begun to question the United States’ reliability, given [President Donald] Trump’s euroskepticism and current President Joe Biden’s handling of the Afghanistan withdrawal. Trans-Atlantic bonds will remain central, but Germany may begin to show a more independent streak.”

No comments:

Post a Comment