Why Texas’ ‘death penalty capital of the world’ stopped executing people

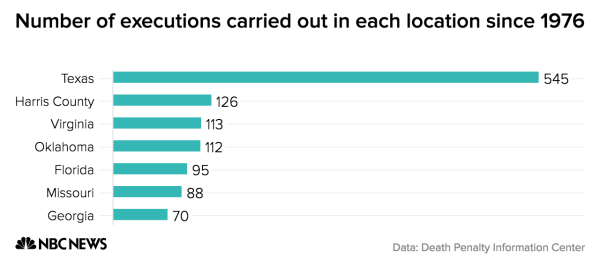

Since the Supreme Court legalized capital punishment in 1976, Harris County, Texas, has executed 126 people. That's more executions than every individual state in the union, barring Texas itself.

Harris County's executions account for 23 percent of the 545 people Texas has executed. On the national level, the state alone is responsible for more than a third of the 1,465 people put to death in the United States since 1976.

In 2017, however, the county known as the "death penalty capital of the world" and the "buckle of the American death belt" executed and sentenced to death an astonishing number of people: zero.

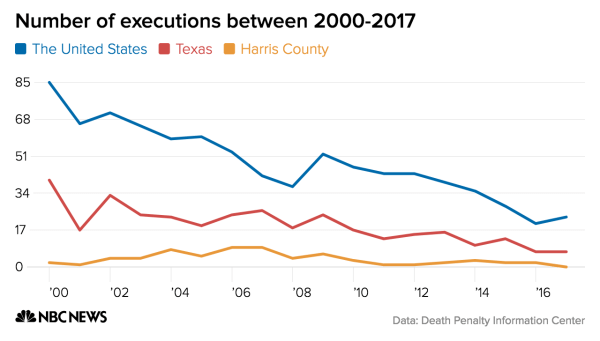

The remarkable statistic reflects a shift the nation is seeing as a whole.

The city of Houston lies within the confines of Harris County, making it one of the most populous counties in the country — and recently it became one of the most diverse, with a 2012 Rice University report concluded that Houston has become the most diverse city in the country.

Under these new conditions, Kim Ogg ran in 2016 to become the county’s district attorney as a reformist candidate who pledged to use the death penalty in a more judicious manner than her predecessors, though the longtime prosecutor didn’t say she would abandon it altogether. Rather, Ogg said she would save it for the “worst of the worst” — such as serial killer Anthony Shore, who was rescheduled for execution next month.

But this year, Ogg appears to have held true to her promise of only pursuing the death penalty in what she deems the most extreme cases. It represents a break from a long pattern of Harris County prosecutors who pushed for the death penalty in nearly all capital cases.

“The overall idea of what makes us safer is changing,” Ogg said. “We’re reframing the issues. It’s no longer the number of convictions or scalps on the wall. It’s making sure the punishment meets the crime.”

Ogg’s approach has earned her recognition from experts, including those opposed to the use of capital punishment.

“She is a much more fair-minded prosecutor than we’ve seen in the past,” said Kristin Houle, the executive director of the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. “She’s very deliberate in her approach to the issues and appears to listen to the concerns of the community. But I think there are still a lot of opportunities for further reform in Harris County.”

Even a state like Texas might stop sentencing alleged killers to death in the near future. And that trend could well extend nationwide.

“We’ve seen a deepening decline in the death penalty since the year 2000, and some states fell faster than others,” said University of Virginia law professor Brandon Garrett, who wrote “End of Its Rope: How Killing the Death Penalty Can Revive Criminal Justice.” He added that the declines are steepest in counties that had sentenced the most people to death.

“Juries are turning away from it, prosecutors are turning away from it, so [the death penalty is] withering away on the vine whether courts or legislators decide to do anything about it,” Garrett said.

She said that her office still has more than 80 pending capital murder cases and she’ll examine each one thoroughly to decide whether the death penalty is the most fitting punishment.

“With other sentencing options and with an increased knowledge of science and technology, Americans feel responsible as jurors in a way they didn’t in the past because there’s more information to be considered,” she said. “So I think attitudes toward the death penalty are changing.”